April 2019 | 1936 words | 7-min read

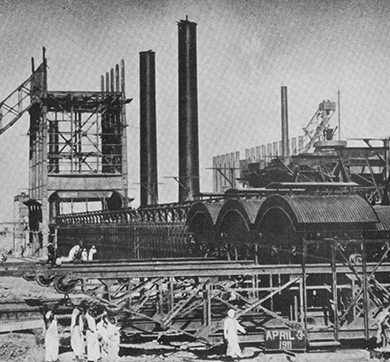

More than 75 years ago, on February 3, 1943, the Howrah Bridge was opened to the public. In those dark days of World War II, there was no opportunity to celebrate the marvellous piece of engineering; a bridge of steel made in India; almost the entire steel produced by Tata Steel and fabricated by Indian engineering firms and built by Indians to a sophisticated international design.

For all purposes, 'Make In India' was born in that era.

It was the amazing foresight, visionary investment in research and development by the early leaders in Tata Steel; India’s technical competence and the confidence in the country’s ability to deliver the fabulous cantilever structure that Tata Steel celebrates today as it rededicates itself to the task of 21st century nation-building.

Read below excerpts from Howrah Bridge: An Icon in Steel, a coffee table book produced by Tata Steel on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the inauguration of the bridge in 2018.

An Emotion Writ In Shining Silver

Three young lads, Sangram, Tapas and Bishu, sure-footed as arboreals, traverse the majestic latticed expanse of over 457.50 metres. They are checking the pulse of this lifeline to the city of Kolkata, its iconic Howrah Bridge. They inspect every nook and corner for any tell-tale sign of potential harm to the bridge; from bird nests to any suspicious corrosive ‘brownish red’ stain.

For this bridge is theirs for safekeeping; it is not merely a bridge for passing but an emotion writ in shining silver. Made in India; skill India…it all began with the Howrah Bridge, says Ashoke Chatterjee, a design guru and the acknowledged master of India’s creative space, who has literally “experienced” the bridge since the age of 10.

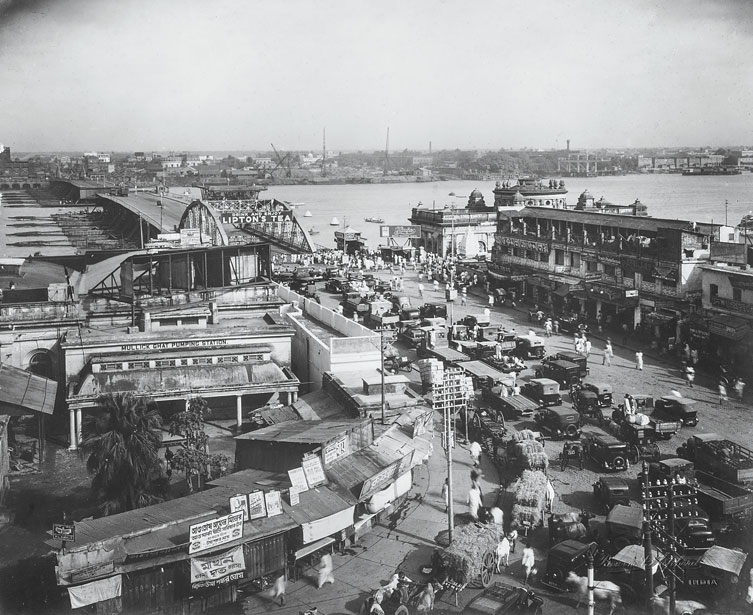

For most of 21st century Bengal, focused on its “glorious past”, this is the 20th century engineering marvel that could only have been possible in ‘Calcutta’; the colossus, straddling the Hooghly, a distributary of the mighty Ganges. For such others as the celebrated but irreverent Geoffrey Moorhouse, it was something of a monstrosity: “There never was a bridge that dominated a landscape as much and in so ungainly a fashion as this one”. Yet other equally discerning European observers have been quite wonderstuck by its majesty with a Frenchman likening it to a supine Eiffel Tower. The sight of the bridge deck hanging from 39 pairs of hangers suspended from the main trusses is quite mind-blowing.

For the average citizen of this passionate city, it is a magnificent obsession; as it is for the global aficionado. Even Herge’s Tintin finds himself placed before the Howrah Bridge, on the Facebook page of the Belgian Embassy, without the boy detective ever having visited the city. In its early years, any Bollywood depiction of “Kullkutta” had to include the silver festoon across the city’s skyline.

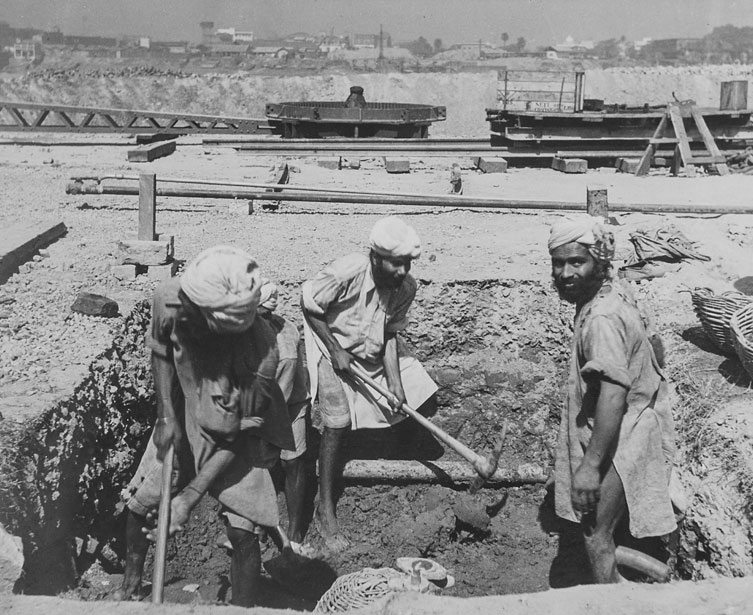

The Technology apart, the Howrah Bridge was built in an environment of religious bonhomie between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. There were also the Nepalis, Gurkhas and even Pathans making valiant contributions. Every festival was celebrated with great gusto, bringing work to a halt.

It was all taken in good spirit and never was a day lost to labour trouble of which the city was beginning to get a taste. They were the unheralded heroes working under the overall supervision of Britain’s technology experts.

Today, the young trio is the unheralded hero of the bridge…

Almost unheralded as the bridge itself that was thrown open to the public of ‘Calcutta’, as it was then called, in the dead of the night on February 3, 1943, a tramcar rolling down from the city end to the station end. Not even the registers of the Port Commissioners dared log an entry.

The Eerie Silence

For a technological marvel that had given rise to much discussion in technology circles the world over, ever since the designs—for what was then to be the longest cantilever bridge—were being worked on, the eerie silence upon completion was a testament to the terrifying oppressiveness of war. The Howrah Bridge was the targeted bridge for a bombing. The Pearl Harbour experience weighed heavily on every mind.

1943 ‘Calcutta’ was in the vortex of World War II and the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was eyeing the looming silver structure. Japan had taken Burma some nine months ago and ‘Calcutta’ was as lucrative a target as any other.

Bombard the city they did on December 20, 1942, and again but, destined for great glories, the set-to-be-inaugurated Howrah Bridge managed to stay out of the air-raiders’ radar. “I remember the bombing of Calcutta by the Japanese, the target being Howrah Bridge”, said Katyum Randhawa, then a young Parsi girl, in a later submission to WW2 People’s War.

Coming into ‘Calcutta’ in 1945, Ashoke Chatterjee, now 83, found this incredible structure with what seemed to have “dirigibles” flying above it. These were barrage balloons, large kite balloon, used to defend installations against aircraft attack by raising aloft cables that created a collision risk and stymied the bomber’s intentions. By 1938, the British Balloon Command was set to work to protect industrial areas and cities, ports and harbours.

The Howrah Bridge was thus decked up in protective gear for war. “They looked like Zeppelins to a child”, recalls Ashoke Chatterjee...

Enter Tata Steel

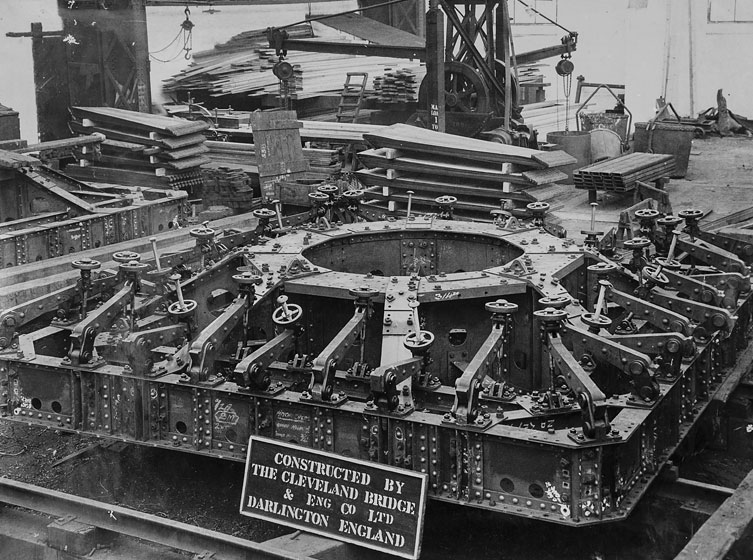

An Indian enterprise was ready with the ability to supply steel to the required specifications. It had earlier proved its credentials as had local engineering fabricators in the construction of the £450,000 (Rs 60 lakh) King George VI Bridge. Evidence of this is to be had on Page 12, of the Engineer of January 7, 1938.

Under the head, Asia, it recorded: “Late in the year a new railway bridge over the river Meghna at Bhairab Bazar, in Bengal, was formally opened and named the King George VI Bridge. All the steel work, amounting to some 3,400 tons, was manufactured by the Tata Iron and Steel Company”.

The fabricators were Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Company (BBJ) and the consulting engineers, Messrs Rendel, Palmer and Tritton, of Westminster.

The archives of Rendel Palmer and Tritton say:

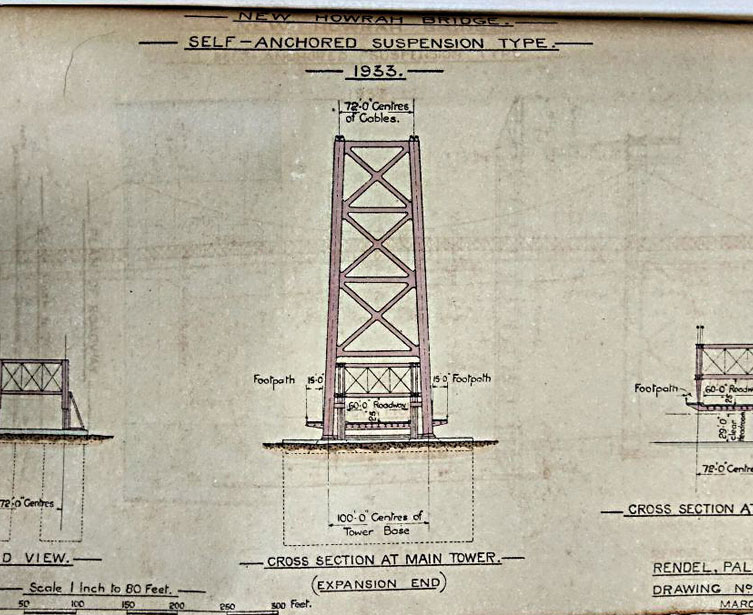

“James Meadows Rendel, the 6th President of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) 1851–1853 formed Rendel & Partners in 1838 in London, U.K. The company later changed its name to Rendel, Palmer & Tritton”. This was the company that was asked to design the cantilever bridge of 1,500 feet span, with a fixed height, a 71 feet wide roadway with two 15 feet cantilever footways. In doing so, it also considered navigational aspects at the Hooghly, hydraulics and its tidal conditions.

Its report was available by 1929 and commented upon by the technical media.

How Tata Steel Delivered

High-tensile structured steel had by then proven itself. The 1933 estimates for a self-anchored suspension bridge and, optionally, for a comparable cantilever bridge, clearly demonstrated their faith in the strength and value for money propositions of high-tensile structured steel.

The official cantilever design made use of such high-tensile steel wherever it would deliver lower costs. Nevertheless, the design specification was effectively drawn up to cover the use of both ordinary structural steel to BSS 153 and high-tensile structural steel having an ultimate tensile strength of from 37 tons to 43 tons per square inch, “a yield-point of not less than 23 tons per square inch, and an elongation of not less than 18 per cent”, said Maurice and Bateson. These values for high-tensile structural steel are the same as those subsequently adopted in BSS No 548, in 1934. High-tensile rivet steel was specified to have an ultimate sheer strength, on driven rivets, of 26 tons per square inch.

How did Tata Steel manage to deliver to the required specifications? Of course, the participation became possible thanks to the metallurgical department for process control started by the company in 1925, which was constantly improving steel quality and addressing customer feedback. By the time the bridge was being built it had a fully-fledged research and control laboratory that was formally inaugurated on September 14, 1937 by Chairman, Sir Nowroji Saklatvala, and Sir M Visvesvaraya.

Such guiding visionaries were inspiration enough but the department received further impetus when the company was tasked with making a suitable low-alloy structural steel for the New Howrah Bridge Tata Steel records show that the final specification called for the use of high-tensile structural steel having a specified tensile strength between 5.82 and 6.77 metric tons per square millimeter (37 and 43 tons per square inch—1 kilogram is equal to 0.001 metric tonnes, or 0.00110231 tons) and it had to launch a comprehensive R&D initiative to produce steel that would comply with the specifications. The going was not easy and there were difficulties galore though none that its metallurgists and engineers could not overcome.

There were problems with the rolling of sections in the mills. The degree of spread of the steel under the rolls was different from the plain carbon steel. Roll pass designers had to step in and to modify the pass design so that it was possible to roll sections in this special alloy steel quality as well as in plain carbon quality on the same roll-setting. “If they had to rely on import of steel, the construction would have been enormously delayed. Even during this period, Tata Steel had to sell steel to support the war effort; steel was sold at controlled prices! Sir Jehanghir Ghandy was knighted because of this contribution”, says Dr Tridibesh Mukherjee, former Deputy Managing Director, Tata Steel. “The name Tata Iron and Steel Co is embossed on the steel structural”, he says.

Excerpted from Howrah Bridge: A Icon In Steel, (2018) published on the 75th anniversary of the inauguration by Tata Steel.