February 2023 | 3079 words | 12 minutes

For the Tata group, the nation has always been at the heart of business. And the roots of this can be traced right back to the Founder Jamsetji Tata.

Jamsetji came of age in an India that had just begun her mutiny against the British rule in 1857. Though he never took an ostentatious part in politics, the advancement of his country became core to his endeavours. He believed that he would better serve India by heralding its industrial revolution and economic liberation. To him, his country’s industrial progress was to be the vindication of her demand for self-rule, self-governance and growing aspirations.

“Jamsetji was a nationalist long before this word had any real significance,” Tata group historian RM Lala noted in The Creation of Wealth. “His nationalism, however, was not narrow. It was, like Tagore’s, rooted in his love for humanity, arising out of his passionate love for his own land to which he harnessed creative forces of his genius. Every day of his life, therefore, became a preparation for that time when his country would be in charge of her destiny. When he surveyed the untilled industrial field of India, he perceived the benefits it could gain through science and technology. Not only did he grasp the full significance of the industrial revolution of India, but his clear mind spelt out the three basic ingredients to attain it. Steel was the mother of heavy industry. Hydroelectric power was the cheapest energy to be generated. And technical education coupled with research was essential for industrial advance. This may be obvious to us today, but it was not so a century ago to a nation subjugated to a colonial economy. In Jamsetji, India had found a man of ideas with the ability to translate them into reality.”

Patriotic entrepreneurship

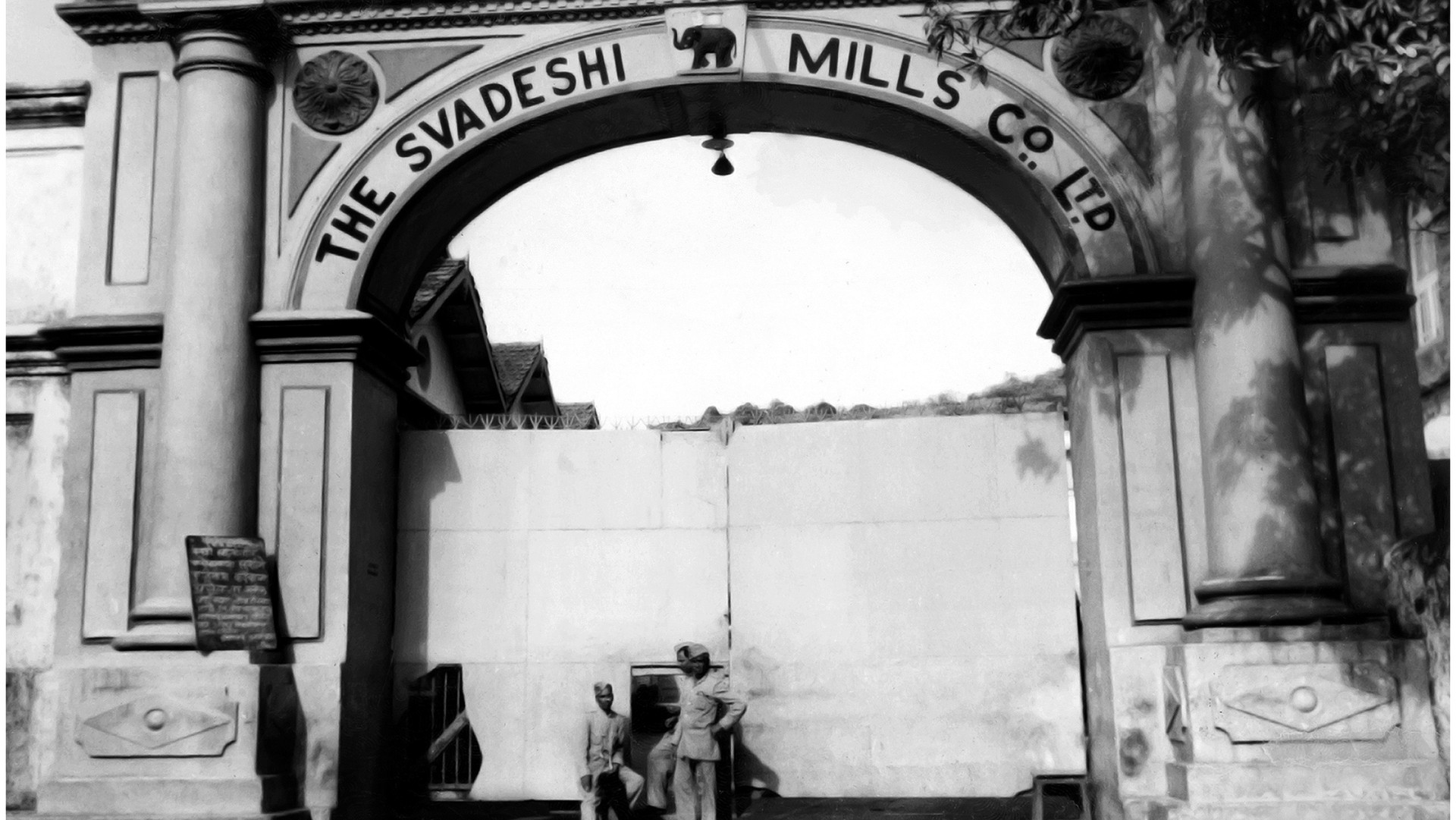

The concept of swadeshi appealed to Jamsetji. Long before India’s Swadeshi Movement became a political cry in 1905, he had found his own ways to further the cause of ‘India for Indians’. In 1886, he purchased a sick mill against expert advice and rechristened it Svadeshi Mills — with the will to produce textiles so fine that they could compete with British goods.

This proved to be one of his most difficult projects, running into heavy losses. But Jamsetji remained undeterred. He poured everything into it, even his private funds, until his efforts paid off. Within a decade, Svadeshi’s yarn fetched the highest prices in the Far East market and became one of the few that could successfully compete with the best yarn that Britain’s cotton mills could spin.

Jamsetji then set his sights on building a hotel worthy of not just his beloved city of Bombay (now Mumbai) — which only had basic facilities, irreputable taverns and hotels for Europeans at the time — but also his country.

Lovat Fraser, a friend of the Tatas whose words were documented in The Taj at Apollo Bunder, said, “I once wrote an article in which I said that the man who built a hotel worthy of such a city would do more for Bombay than the donor of many museums. He came to me and told me that the idea had long been simmering in his mind, and that he had made much study of the subject. He had not the slightest desire to own a hotel; however, his sole wish was to attract people to India, and incidentally to improve Bombay.”

Using his personal money, and not that of the company, Jamsetji acquired a parcel of land by the Arabian Sea and set about constructing the “best hotel east of the Suez”. He even embarked on an overseas buying spree, scouring New York, London, Paris, Dusseldorf, Berlin and other cities, for the most modern equipment that could be procured. The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, its original name, opened its doors on December 16, 1903, giving India its first luxury hotel and a landmark that put the country on the world map.

Silent force for swaraj

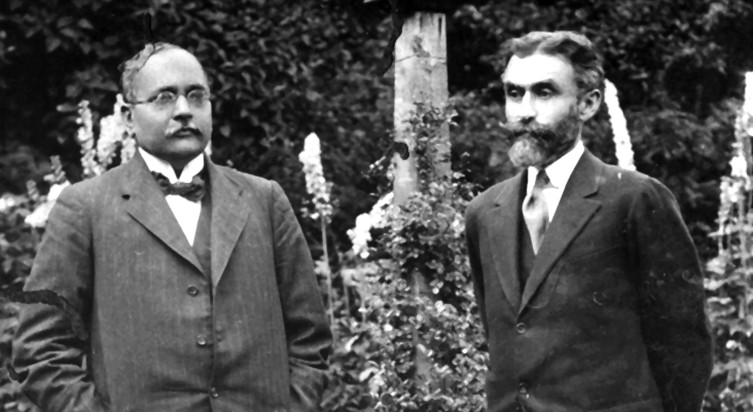

Jamsetji Tata’s political views were shaped in the presence of stalwarts like Dadabhai Naoroji, the Grand Old Man of India, and Pherozeshah Mehta. He joined Mr Mehta in starting the Bombay Presidency Association, a leading political outfit. He was also present at the first session of the Indian National Congress and supported their endeavours towards India’s freedom to the end of his life.

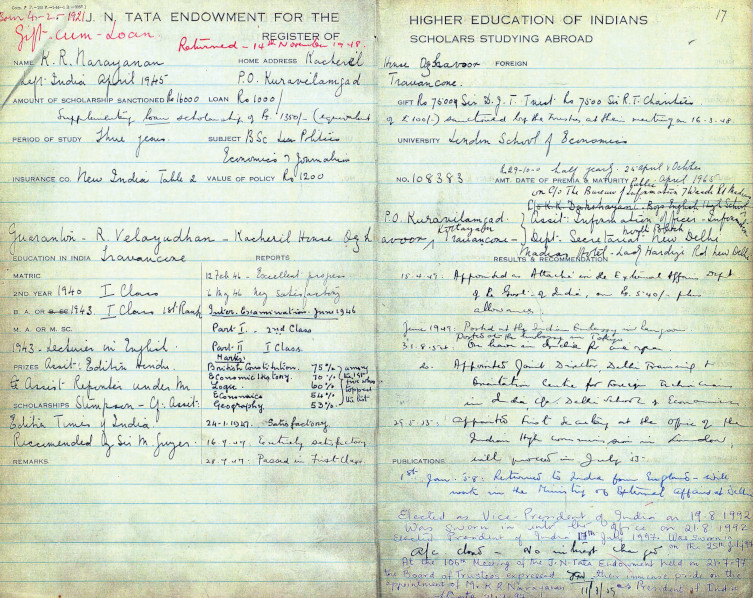

Jamsetji had the foresight to know that self-rule could be facilitated through self-administration and put into motion a system that could make it happen. Pre-independence India was administered by the Indian Civil Service (ICS), which was largely made up of the British. The standard of education then available in India and the cost of education in England made it very difficult for Indians to enter the service. Perceiving the need to give advanced education to Indians in science, engineering, medicine, the humanities and administration, Jamsetji launched the JN Tata Endowment for the Higher Education of Indians in 1892. Of the 19 scholars awarded the benefit in 12 years up to his death, 10 were for studies for the ICS.

His objective was primarily to train Indians to administer themselves, and by 1924, 20 percent of the Indians in the ICS were JN Tata scholars.

As Mr Mehta said, “The current notion that Mr Tata took no part in public life, and did not help and assist in political movements, was a great mistake… The help, the advice, and the co-operation which he gave to political movements never ceased except with his life.”

Into the league of industrialised nations

“While many others worked at loosening the chains of slavery and hastened the march towards the dawn of freedom,” former Indian President Dr Zakir Husain once said, “Jamsetji dreamed of and worked life as it was to be fashioned after liberation.”

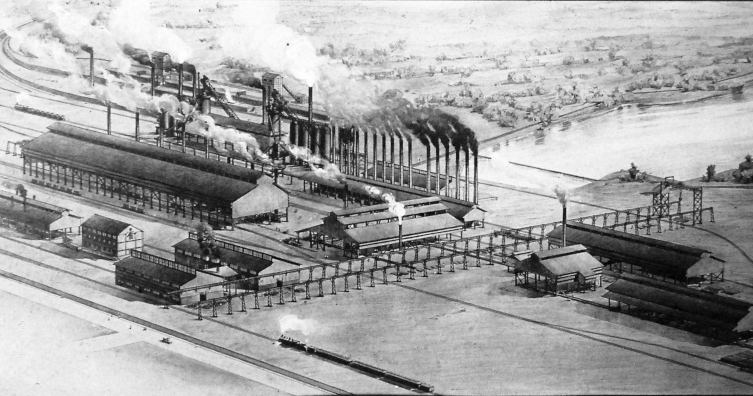

In his lifetime, Jamsetji created the blueprint to propel India into the ranks of industrialised nations by manufacturing steel and harnessing power. His heirs, son Sir Dorabji Tata and cousin RD Tata, brought them to life.

In 1907, they established the Tata Iron and Steel Company (now Tata Steel), which held the distinction of being India’s first integrated steel company. It was a truly swadeshi enterprise, financed by swadeshi money and managed by swadeshi brains, which produced world-class steel and gave Indian industry the momentum it needed.

“So far, we have but scratched the surface of this great land,” Sir Dorabji told shareholders. “Is it not time that all of us should do something within our individual, humble spheres to raise metaphorically two blades of corn where one grows; produce out of the fullness of our own land, and with our own labours… something that will raise the comfort and the standard of the people; something for which those who come after us in life will be happier, healthier and more prosperous than we are today? Is it not time to stir ourselves, to wake up to the great opportunity and the stern duty before us — the task of India’s industrial regeneration?”

In 1910, Jamsteji’s heirs established the Tata Hydroelectric Power Supply Company (now Tata Power) to supply cheap and clean electricity to Mumbai, putting their faith in renewable energy way before it became a talking point. By 1911, they had raised enough Indian capital to lay the foundation stone of the first dam, an occasion that compelled the then British governor of Bombay to note, “This project symbolises the confidence of Indians in themselves.”

Bequeaths to a nation

Along with industry, Jamsetji Tata was a pioneer in another direction. He set the Tatas and India on the path of constructive philanthropy in life and beyond.

Just like he set up the enduring JN Tata Endowment for the Higher Education of Indians in his lifetime and bequeathed money for the establishment of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), his sons too donated generously. Sir Ratan Tata’s will brought about the creation of the Sir Ratan Tata Trust in 1919, one of India’s oldest philanthropic organisations. Sir Dorabji Tata left most of his personal wealth to the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust formed in 1932. Together, with other trusts established by the family, they form the Tata Trusts.

Manufacturing swadeshi care

After fulfilling the dreams of his father, Sir Dorabji furthered the nation’s march towards industrial development and self-sufficiency with forays into new industries.

With the establishment of the Tata Oil Mills Company (TOMCO) in 1917, he marked the group’s entry into the consumer and retail segment. The company produced iconic personal care products like Hamam soap. Started in a township near Cochin (now Kochi) in Kerala — which came to be known as Tatapuram — the company not only brought industrial wealth and well-being to an underdeveloped area but also change. The Tatas, who had offered employment to women since the time they set up their first textile mill in the 1870s, opened employment to women in TOMCO’s laboratories and administrative offices. At the outset, the move faced considerable resistance from men. But the Tatas refused to back down, bringing reform to the community.

In 1919, when the insurance sector in India was dominated by foreign companies, Sir Dorabji established the New India Assurance Company (1919), the first wholly Indian-owned insurance company. “It is not a Bombay insurance company or a company working solely in India but may claim to be a worldwide company,” he had told shareholders. “It is anticipated that a very large proportion of the income in future years will be obtained outside India.” By the time the life insurance sector was nationalised in 1956, New India Assurance was operating in 46 countries outside India and was one of the largest composite insurers in the east. It is today the largest public sector general insurance company of India.

During his tenure at the helm of the Tata group, Sir Dorabji also established the Indian Cement Company (1912), the first successful attempt at producing cement in India; the Tata Industrial Bank (1917), a first-of-its-kind institution to develop industrial resources of the country with Indian capital; and the Tata Construction Company (1920), which dented the British monopoly of massive infrastructure projects. It was also during his time that India’s first airline, an aviation unit pioneered by JRD Tata, took wing.

The third dream

Jamsetji Tata believed that technical education and research were as fundamental to economic progress as steel and power. He set in motion plans for a world-class institute to meet this need and willed a vast portion of his personal wealth to execute them.

The IISc opened its doors in 1911 and became home to some of India’s most brilliant minds. Nobel Laureate Sir CV Raman became the first Indian director of IISc in 1933. Other eminent scientists of IISc included Homi J Bhabha, the founder of India’s nuclear programme, and Vikram Sarabhai, the founder of India’s space programme.

Jamsetji’s successors built on his vision by establishing the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (1936), which marked the beginning of social work education in India; and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (1945), which went on to build India’s first digital computer.

The next frontiers

JRD Tata, who took over as Tata Sons Chairman in 1938, shared the Founder’s belief in the power of industrial development. “Where others thought primarily or exclusively in terms of political action, he saw clearly that India’s freedom could not be achieved or maintained by political means alone, that freedom without strength to support and, if need be, defend it, would be a cruel delusion and that the strength to defend freedom could itself only come from widespread industrialisation and the infusion of modern science and technology into the country’s economic life,” JRD wrote about Jamsetji.

JRD took the Tata group and India into the next frontiers of travel, science and engineering with Tata Air Services (now Air India), Tata Chemicals, and Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company (TELCO, now Tata Motors).

He established Tata Air Services in 1932 with a deep faith in the future of the country’s air transport potential. Just 100 days after piloting the inaugural flight of India’s first airline, he had said, “I want to express, perhaps unnecessarily, the unbounded confidence we have in the ultimate future of air transport in India. A few lean years will precede the great development that must come but that has always been so with any new enterprise. … We look forward confidently to the day when none of you will think of travelling or sending your letters by any other way than by air, and when this time comes, if we have done our bit in helping India to make up for lost time, and to attain a position in aviation worthy of her, we shall have achieved our purpose and we shall be satisfied.”

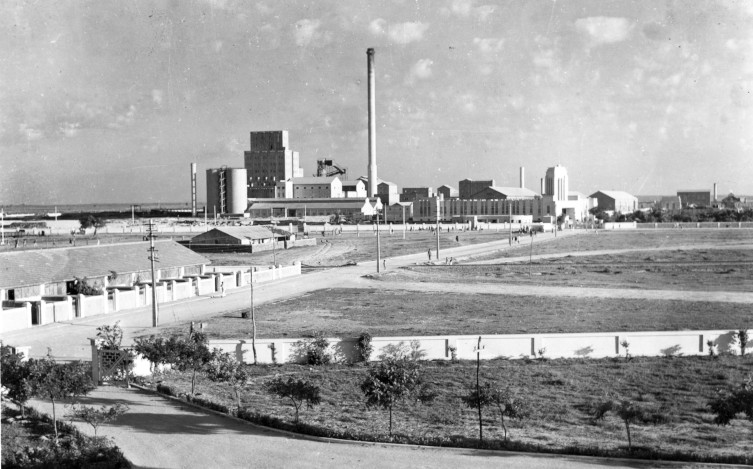

In the 1930s, the Tata group was also considering an entry into the chemical industry. India was wholly and detrimentally dependent on imports for soda ash, caustic soda and other soda compounds that are integral to the manufacture of a wide range of products from soap to glass and textiles — so much so that a Tariff Commission report had stated that for India to become industrialised on a considerable scale, the establishment of a chemical industry was a matter of great importance. “In 1937, Tatas received a proposal from the State of Baroda to start a chemical industry at Mithapur, and in 1939, Tata Chemicals was launched,” says The Creation of Wealth. “Its engineers cracked the code for soda ash manufacture, giving India an important base for its industrialisation, next in importance only to steel and electricity.”

As the decade turned to the 1940s, and the idea of independence seemed close enough to grasp, JRD knew that a newly independent nation would also need a stronghold in engineering to flourish. In 1945, Tata Sons set up TELCO in Jamshedpur, which started with steam locomotive boilers but quickly went on to manufacture road rollers, complete locomotives and more — all engineered to move the country forward from the “stroke of the midnight hour” on August 15, 1947.

From satyagraha to swaraj

While the Tata group stood at the frontline of preparing India for economic independence, it also stood in support of the country’s political independence and self-determination in several seen and unseen ways.

Seeding satyagraha

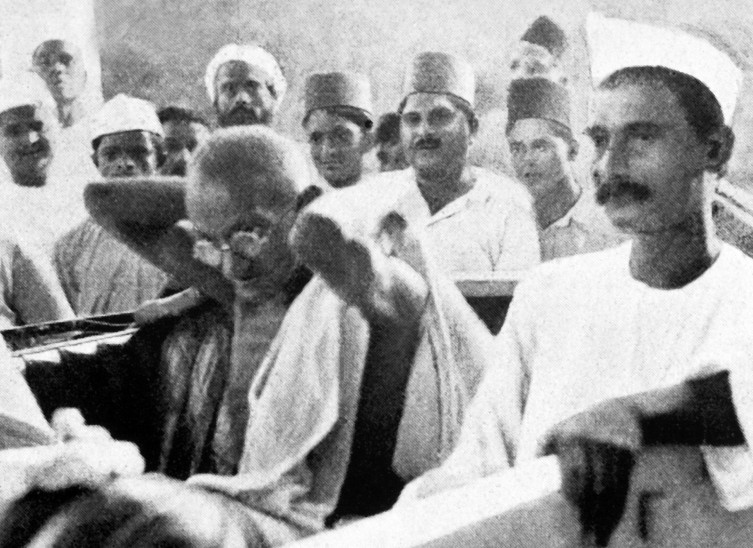

Sir Ratan Tata was among the first prominent Indians to support Mahatma Gandhi’s first satyagraha, when the latter was just a lawyer fighting for the rights of Indians in South Africa. Sir Ratan made a first donation of Rs 25,000 in 1909, a second donation of Rs 25,000 in 1910, and a third donation in 1912. These were crucial to the survival of the Phoenix Settlement, the birthplace of satyagraha. “He has made the lot of passive resisters easy,” Gandhiji wrote in the Indian Opinion, the mouthpiece of the satyagraha, after the third donation, “and the fact that there are at the back of the struggle such distinguished Indians, encourages those who are engaged in it, and probably brings them nearer their goal.”

He never forgot the support. On a visit to Jamshedpur to support the Tatas in 1925, by which time the nation regarded Gandhiji as the Mahatma, he said, “It would be ungrateful on my part if I do not give a little anecdote about how my connection to the Tatas began. In South Africa, when I was struggling along with the Indians there in the attempt to retain our self-respect and vindicate our status, it was the late Sir Ratan Tata who first came forward with assistance.”

Spinning swadeshi

The Tata support to India’s freedom struggle also came from Sir Dorabji Tata’s wife Lady Meherbai Tata and RD Tata. Lady Tata started learning spinning in 1919 to promote the activity — a key part of Gandhiji’s Swadeshi Movement — as profitable and respectable. Meanwhile, RD Tata, who believed in the ultimate freedom of India, aided Gandhiji’s vision of self-reliance and self-rule by providing 1 lakh spindles and other spinning supplies to support the Swadeshi Movement. Lady Tata also championed Gandhiji on global platforms through her speeches, like at Battle Creek College in America in 1927.

Supporting swaraj

As the freedom movement gathered steam, the Tatas continued to play an essential supportive role. Leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel often gathered at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel and conferred about the next steps to be taken for the freedom movement.

According to The Taj at Apollo Bunder, “Despite their consciously European image and largely European clientele, these were among the few places in the country where Indians and Englishmen could meet as equals, under the aegis of such informal bodies as the Young Europeans and the European and Indian Progressive Groups.”

The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel was also the venue of the historic meeting of the Congress and the Muslim League in January 1916, which led to the joint declaration that “India should be lifted from the position of a dependency to that of an equal partner in the Empire with self-governing dominions”.

The support of the Tatas was recognised by several leaders of India’s freedom struggle through words and actions, including Gandhiji, who said, “May India produce many Tatas.”

—Monali Sarkar

Photographs by Tata Central Archives, Tata Steel Centre for Excellence