July 2019 | 5825 words | 22-minute read

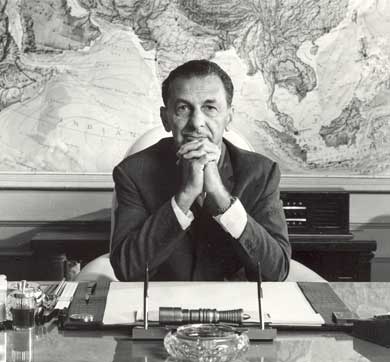

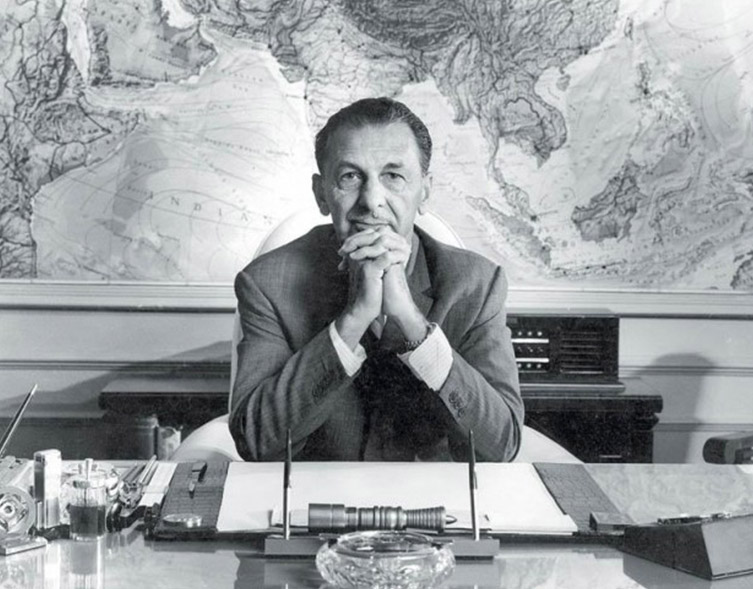

An oral history recording of JRD Tata with MV Kamath, in which the former chairman discusses life growing up in France, India and Japan, how his Parsi father and French mother shaped his character, his time in the French army, and finally, his journey to the Tata group and his chairmanship. Excerpts follow:

Where was your father born and have you any memories of your paternal grandparents?

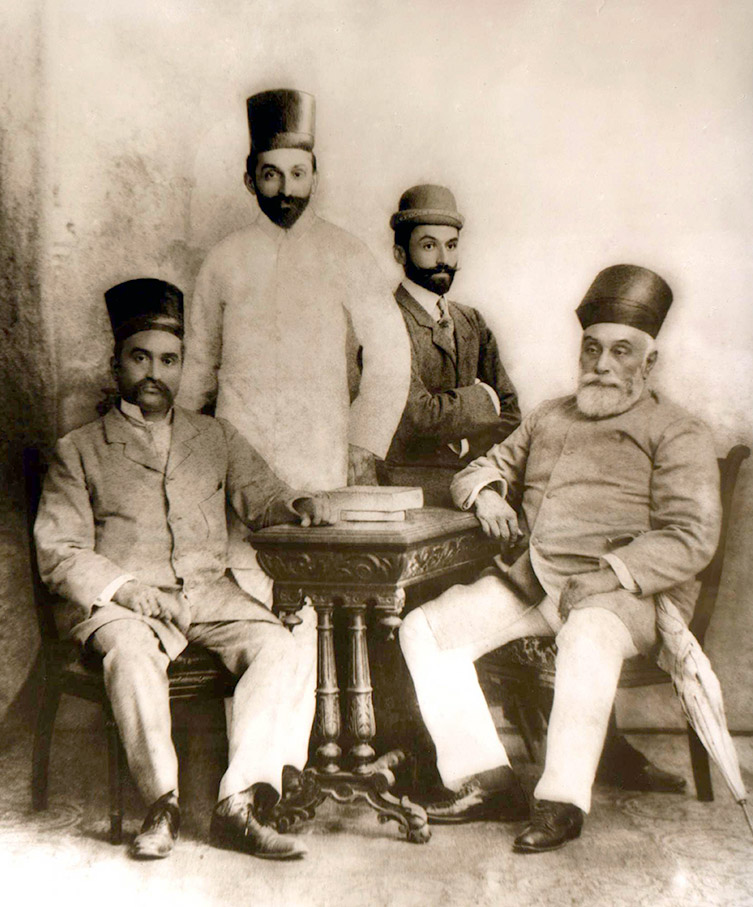

I do not remember any relatives or parents of my father. He was born in Navsari from a poor family and as far as I know he was an adopted son. Among the Parsis, it is quite a common practice for a family if it does not have a son, or if they would like to help out some youngster who happens to be particularly bright or is directly related, to adopt him. So, as far as I know, my father was himself an adopted son, probably because his father had died or he was an orphan.

In 1902, at about 46, your father married a young French girl he got to know in Paris. How did it begin?

Father got a liking for gems and decided that he would like to go to Paris. Once he was there, he decided that he would like to learn to speak French.

He had some Indian friends try and find him someone who would teach him. It must have been 1899 or 1900. His friends recommended a French lady called Madame Briere, of a fairly high middle-class family of artists and professors. She had a daughter, born in 1880; that was my mother. Evidently, my father, who by that time was 44 years old, must have fallen in love with this lady, this very talented young lady, and proposed. It must have created a bit of a sensation, and my grandmother, who was a very intelligent woman – and who must have found it extraordinary to have a young daughter married to someone from such an exotic and strange country like India, who did not believe in the same god – evidently agreed.

"A view about one’s father, and a wonderful father that he was, are always subjective. To me, he was a man who saved the Tata and Steel Company."

They got married in 1902. My mother, during World War I, served as a voluntary helper in an American hospital in Paris for the wounded. In fact, during the Battle of the Marne, which was quite near Paris, quite a lot of wounded were coming to Paris. In the course of working there, she seemed to have got tuberculosis, which ultimately ended her life many years later, in 1923, when she was still a young woman.

In those 21 years she produced five children. These years were rather exciting years because World War I came along, and in any case, we used to live partly in France and partly in India. So, every two years my family – not my father – led by my mother, used to change homes.

My father did not have money – he was rather a spendthrift – and so he earned well. There were no taxes in those days. But he spent most of what he earned. He never had a home of his own until right at the end of my mother’s life. He built a house for her in Bombay, but she died in 1923 before it was completed.

"My mother, during World War I, served as a voluntary helper in an American hospital in Paris for the wounded."

Your grandmother must have been a very extraordinary person. Can you tell us more about her?

She was a formidable lady. She had very strong likes and dislikes, and whose pet hate was, of course, Germans, because she went through three wars against the Germans. By the last war, in 1940, she was already 90 years old. By that time, probably her mind wandered. I think the old lady fell in love with (the idea) of Marshal Petan, who was himself about 90 and a great hero of France. Therefore, Marshal Petan could do no wrong and when he surrendered to the Germans, she decided that there must be a good reason and the reason she found for herself was that it was the fault with the British and that the British wanted to capture the colonies of France, some silly idea like that. So, she died no longer anti German. But otherwise, during her lifetime, she was really a very difficult person.

How did she treat you? How were your relations with her?

She was very, very fond of her grandchildren, particularly my younger brother who died recently (Darab). She was a very interesting and capable woman. Highly educated, and really was responsible for the high standards of education of my mother.

She accepted a stranger; a Parsi from outside required a deal of adjustment.

Well, I don’t think she was consulted. My mother was very independent and forthcoming and she decided if father wanted her to become a Parsi she would become a Parsi. It created a storm in India, and there was a long-drawn battle in courts about whether a non-born Zoroastrian can become a Zoroastrian. In the end, father both won and lost the case.

What are your early memories of your mother?

Wonderful memories of great love and admiration. She was a beautiful woman, an extraordinarily beautiful woman. Also, among the talents of being a wonderful wife and mother, she also had an ability to cart up to five children from one place to another, finding homes and ruling the family with love and a very great efficiency. She had a wonderful voice. She used to sing in amateur performances.

When she used to come to India, how did she adjust to the food, climate, water, etc? Did she at any time have difficulties?

She wrote detailed letters to her mother weekly about what was happening and (she was) extraordinarily adaptable. After all, coming to Navsari, seeing my father drink toddy from an earthen pot, walking about barefooted. At first my mother was astounded, then greatly amused. She got on extremely well with the locals, (and adopted) habits (of the) Parsis. She spoke Gujarati, and English, not so well.

Was it an Indian style of living in those days, such as sitting on the floor?

Since my father had married a European lady, he saw to it that he had the kind of furnishings and life that she was used to. But there was no problem about putting a mattress on the floor when in Navsari and sleeping on it. She was a very adjusting lady.

What did you inherit from her by way of qualities?

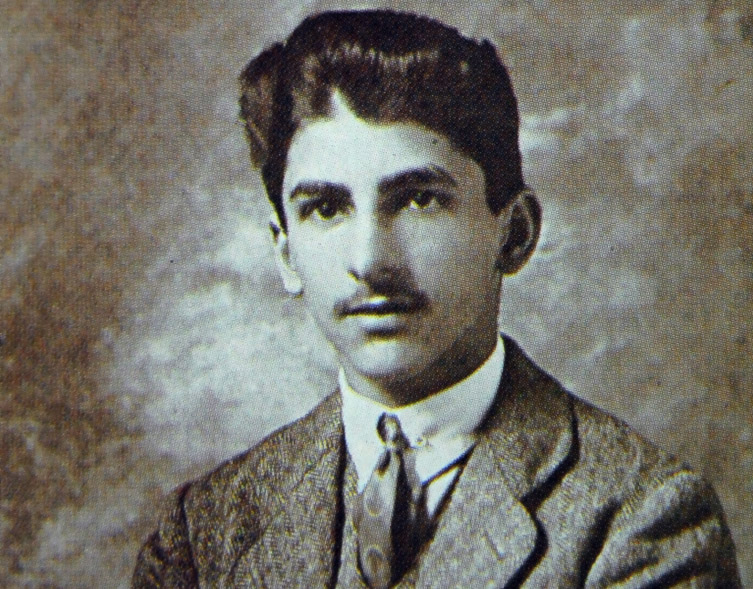

I think love of poetry, love of music. Unfortunately, she died when I was very young. I was there at the time of her death. She had been ill back and forth until the last year she was quite ill in France. She died in 1923 when I was 19 years old. There was a time when I was away in the French Army and for a year in England. So I always regretted that I did not spend more time with her and my father.

"(I have) wonderful memories of great love and admiration (of my mother). She was a beautiful woman, an extraordinarily beautiful woman."

Did you miss her a great deal when she died?

Yes, and also my father. He died in 1926 when I was 22… so I lost both my parents very near each other.

What kind of relationship did you have with your father?

Unfortunately, not close enough because I guess he was a much older man. He was very busy and worried about Tatas and Tata Steel, and so he used to work long hours. Go to office early, come back late and although I was very fond of, and greatly admired him, he did not have time for a really close and leisurely relationship. Whenever we were in Europe, father would appear for a month and then come back to India. We were as close as could be but not in practice. We never interfaced as much as we would have liked to."

"(My rank was) second lowest. Second Class Sepoy. In fact, I had a meteoric career from Second Class Sepoy to Air Commodore in the Indian Air Force."

What do you remember best about him?

A view about one’s father, and a wonderful father that he was, are always subjective. To me, he was a man who saved the Tata and Steel Company. He was a workaholic only because the work needed him. It deprived him of his life with his wife and his children and so he spent far less time with his family than he would have liked.

You lived first in Paris, then in Bombay, then again sometime in Japan. Can you give us a chronological sequence of your stay in various places to the best of your memory?

Whenever I was in Bombay, I was at the Cathedral High School. When I was in France, I was admitted to one of the top public schools in Paris called Janson de Sailly. Every time I went back to France, I’d re-join a different class. This made it a bit more difficult than it need have for me.

I’d first been educated in English – I wasn’t very good in English, at least in pronunciation. I’d suddenly find myself educated in French. I wanted to go to university, and it had been arranged that I should be admitted to one of the colleges in Cambridge.

But so far as India is concerned, it was British education in India, in high school. In Cathedral, they used to teach you English, and English history. You didn’t learn Indian history, you learnt British history, and British literature. I could hardly consider myself as educated enough to enter university.

So, in order to get admitted I was sent to a Crammer on the east coast of England. A Crammer is an establishment for boys whose education up to then – either they’ve been lazy or they’ve been like me, cramming enough to be able to pass the entrance examination. I went there in England in order to learn English properly, and also to prepare for the entrance examination to Cambridge.

That was in 1925. I spent a year at the end of my military service because I had a dual nationality. I was born a French man in France and was treated as a French man. In India, as an Indian. A British subject presumably. My father was very grateful to France for having given him my mother.

My father wanted me to – as every young man in France at the age of 20 had to – spend a year and a half, at times it used to be two years, in the military service in France. That was in 1924, when I was 20. So, half of 1924 and a half of 1925 I was in the French Army. I was in the cavalry.

I made use of my grandmother but not very successfully. I wanted to learn how to ride well, thinking that maybe one day in India, if I’d have enough money, I’d be able to play polo. My grandmother apparently knew a French General. Out of kindness to her, he ensured that I’d be enlisted in a Cavalry Regiment.

Unfortunately, he got me into an Arab regiment that was mainly in Tunisia and Algeria, but also having some of their regiments in France. The bulk of the soldiers were either Algerians or Tunisians. We used to ride Arab horses. Arab riding is completely different from European riding. Whatever I learnt of riding in the army was of no use to me for playing polo or even riding for pleasure. Because I was the eldest son of a family of five children, I was allowed six months less. So instead of a year and a half, I had a year.

The regiment was called Le Spahis, which is the Sepoys. So, I was a sepoy, except that I had an attractive uniform.

"Officers used to come and ask me to type a letter of application for leave or for something and they gave me a tip of 1 franc, which I always accepted with a very polite 'thank you very much'."

What was your rank?

Second lowest. Second Class Sepoy. In fact, I had a meteoric career from Second Class Sepoy to Air Commodore in the Indian Air Force. The point I was making, which was of some relief – life in the barracks was pretty primitive. There were no bathing facilities in the barracks. We had to go to town and pay for a bath. Very few bothered to bathe in the French army in those days, including the few Frenchmen who were there.

There were no bathing facilities in the entire barracks?

There were cold taps, and in winter they sometime froze. So, I used to go into town twice a week and pay for a bath. The important point I was trying to make is that living in the barracks, living in the dormitory with all these fellows, the nose and the smells and particularly in winter with the windows closed. In the cavalry you have squadrons. In my squadron, there was a captain in charge of the squadron, who discovered that I could not only write well, but also type.

Where did you learn that?

On a Japanese boat coming back from Japan in 1918.

Typing on a Japanese boat?

I spent 15 days on that boat and learnt to type on their typewriter. When he found that I could type, he got me out of the barracks, out of the dormitories. He didn’t want the colonel of the regiment to know that there was a soldier who could type. He got me to sleep in an office – they put a bed in an office behind his office – where I could be concealed, but it failed. And after a month the colonel found out. I was removed from there and accommodated in the colonel’s…

That’s a real promotion.

That was a promotion, and I used to type here on a very antiquated machine. It amused me sometimes. Officers used to come and ask me to type a letter of application for leave or for something and they gave me a tip of 1 franc, which I always accepted with a very polite 'thank you very much'. So that was that.

To come back to your schooling, I think there was a prize for a composition which you got and some other young man who was sitting…

That’s not very interesting except it shows that I seem to have had some facility for writing whether in French or English. And to my surprise, there was a year in which the final exam included a French writing composition on a particular subject, and some subject of some historical event, so I wrote that and apparently it turned out to be the best because funnily enough, the man in front of me was the grandson of Marshall of Napoleon, and he was the big fellow in front of me, and so when the teacher said you’d be surprised and he pointed towards me, this big fellow got up and started bowing, and the teacher, “Not you, the L’Egyptien behind you.” He could not make out an Indian; to him; an Indian and L’Egyptien were all the same. There I had love of language, love of poetry, whether in English or in French. So I put it into…

Have you written any poetry – in English or in French?

Written, no. I tried to, but you got to keep that up and I didn’t have the talent.

Who were your best friends in school? Do you remember any of them? Are they alive, would they be alive?

Yes, I had some friends. One was the son of Louis Bleriot, the man who first flew over the channel to England and crashed in England when he arrived (because he crashed almost in every flight) and who died trying to duplicate or trying to beat Lindberg across the Atlantic. They were preparing a bigger plane to fly the Atlantic and he died of a very strange illness. Nobody dies of just appendicitis. So I lost him. And then, in the school Janson De Sailly (there was someone with) whom I became very friendly. But during the war he went underground and was untimely captured by the Gestapo and shot. Then there were few other friends – a nephew of my grandmother who was an electrical engineer – but nobody close, no closely bound friendship.

When were you in Japan and what were you doing there?

Well, in 1916, when my young brother was born, she (Sooni Tata) nearly died – the haemorrhage etc – the doctors advised she must head to a better climate. Normally, we would have gone back to France, but ships were being torpedoed and father felt that to send mother, not very well herself, with 5 children there… So where to go? Really, in India, there wasn’t quite the climate that was wanted or they didn’t want to send her too high to Kashmir. As he had done business in Japan and he had Japanese friends, off we went, all of us to Japan, and settled down in Yokohama in 1917. We were there for two years. In order to maintain English, I went to an American school – a Jesuit school.

"I could read and write (English) but I talked like a Frenchman then much to the amusement of British and Indian friends."

You had your education completely interrupted every now and then?

Everywhere.

Where did you pick up your English? At that point you couldn’t have been proficient in English. Were you, at that age?

No, not too well in pronunciation. I could read and write but I talked like a Frenchman much to the amusement of British and Indian friends.

When the first World War started, you were hardly 10 years old. Do you have any memories of that particular period – those four years?

We lived in an apartment almost in the shadows of the Eiffel Tower. I remember there were some air raids. The Germans had these zep planes. They came over with their zep planes hoping to bomb. But the bombs were small. I once saw a zep plane being shot down and in flames. We were there in France, but we came away in 1916 when my mother was pregnant. We were in India from 1915-16 until 1918, after the war was over.

"My regiment was sent off to Morocco to fight Abdel Karim and was ambushed and totally destroyed. There were no prisoners, they were mutilated. So, if I’d been there…"

I was told that you applied for an extension in the French Army?

I am a little ashamed of that. Well, I was a French soldier and I’d been brought up as a French boy so I had a dual patriotism. I didn’t realise that Abdel Karim was a Moroccan chief who rebelled against the French and so the French army fought him. I thought that taking part in a war in Africa with all the romance… I had six months and I decided that it would be rather fun taking part in a war.

And getting killed!

Well I didn’t think that I would have. In fact, I would have been, if I had gone. I asked my father, ‘can I apply for a six months extension? I’d learn a little more riding.’ He said, ‘certainly not, don’t be a damn fool, come back.’ So, I did. Now the interesting thing is that my regiment was sent off to Morocco to fight Abdel Karim and was ambushed and totally destroyed. There were no prisoners, they were mutilated. So, if I’d been there…

There would have been no JRD Tata.

There would have been JRD Tata up to then, but that’s about all. Then I realised later, after all, these people were fighting against colonialism, I should have been wanting to fight for Abdel Karim and not against him.

But did you have that concept of colonialism at that time?

Evidently not. Yes, in India I didn’t like the fact that the British were ruling us, but Morocco didn’t seem to be an independent country. Anyway, it was quite wrong. As I say I feel ashamed of that particular part of my life, but I am glad I didn’t do it.

But did you have any other narrow brush with death?

Only in flying.

Often?

No, really only once, when I was a bit too bold.

Where was that?

To be a good pilot, you had to do acrobatics. As soon as I became licensed, I decided to do some acrobatics. I had been sent solo, which is never heard of nowadays. It was quite wrong. We had an instructor Sir Victor Sassoon had got for us.

"By then I’d learnt in 1929 and I’d got about 100 hours or 50 hours. I said, 'Well let’s try. It must be fun to fly to London'.”

Sir Victor Sassoon created the flying club movement in India. He donated aeroplanes to Bombay, Delhi, Madras and to Calcutta. In Bombay, he got an instructor from the British navy, who used to fly onto aircraft carriers. He did an unpardonable thing: he never taught me how to spin and how to get out of a spin. I had read all the books, I had read every page written on flying and in doing my aerobatic training I’d go very high – 8,000 feet.

That’s not high?

Well, it’s high enough (that) if you do something wrong, you can get out but if you do it low like Sanjay Gandhi did and others, then you hit the deck. In this case, I got into a spin and I didn’t know how to get out of it. I was doing exactly the opposite because when you are in a dive, and if you want to get up, you pull. Instead of that, if you are in a spin you got to first release in order to stop spinning. Anyway, I knew I spun from 8,000 to 1,000 feet and recovered. That was very near. That was one time, the other times occasionally in bad weather flying the mails.

How old were you when you had that spin?

This was in 1929 when I had just started.

Before you had done your trip from London to Karachi?

No, I had never done London to Karachi. That was in the ’30s when the Aga Khan gave a prize of 500 points to the first Indian who within a period of one month would go from India to England or England to India.

And what was your trip?

And so, I had an aeroplane by then that I had bought for £1000 – a Gypsy Moth – and I was flying in India. I was a young pilot. By then I’d learnt in 1929 and I’d got about 100 hours or 50 hours. I said, “Well let’s try. It must be fun to fly to London.”

You had no maps whatsoever?

No, I had to get maps. You had to apply for maps – you got military maps. You could obtain maps from England for all the routes. That was in May 1930, so I flew to London. Well there was no danger there.

To come back just for a minute to your father, I think he was a great practical joker. He had a grand time at Rippon Club, can you mention some incidents?

He had a lot of spirit for fun. He used to tease, but nothing outrageous. When he was in a party, he was a man who liked to pull the leg of people or to play practical jokes, which is not a very intelligent thing to do sometimes.

You don’t have to answer this. By the time one is 20, one falls in love. Did you fall in love with any of the pretty girls in Bombay at the time?

No, I’d decided that when I fell in love I would marry after considering whom I would marry, how I would marry and why I would marry.

Were you so serious at that time?

Yes, I was 26 by which time I felt that I should start raising a family, if I ever did. I wasn’t successful in that sense; I didn’t have any children. No, the answer is no, until I found someone to suit me ideally. I was very Europeanised, I’d lived half in Europe, in Japan, in India and France. I wanted to have a wife who would be as comfortable in India as elsewhere. I was waiting to find a girl who was like me, half-and-half, where there were foreign parents. My wife had an English mother and a Parsi father. She was born in America and educated partly in Italy and spoke Italian.

Very cosmopolitan.

Very cosmopolitan and she was the most beautiful girl. Combining these three things, I said now is the time – before I miss her and somebody else grabs her.

How did it happen? What was the story behind it?

It so happened that I had done a stupid thing. I had bought a racing car and when I brought that racing car into Bombay, the police decided they had to nab me.

Why?

Because here was a man who was going to drive fast and make a lot of noise and all that. On one occasion, there was a crash, a very fatal accident of a Parsi gentleman coming back from Juhu. I had attended the party and the police concocted a case that I was racing with him neck to neck. He then crashed in a tree. I was nowhere near the place at that time.

For this bogus case, I was asked to see a good criminal lawyer. He was the uncle of my future wife. There I saw my wife and her sister and that’s where we got introduced. I was acquitted; Vicaji, my lawyer, had no problem not only demolishing the case but the judge passed very severe stricture on the police. Anyway, that’s how I met my wife.

What was your first assignment on the staff of TISCO and what was Jamshedpur like in the early 1930s?

Actually, it was in 1925-26, a little earlier even than the 1930s. I was not put on the staff of TISCO; I was placed there at the instance or request of my father who was, I think, at that particular time Vice Chairman of TISCO. I was sent there, with the idea that I’d spend a couple of years at Jamshedpur. Since I had not been trained as an engineer or had no formal education, I should learn the practical aspects of the steel industry. The sole purpose was that I would spend a month or so one after the other, in every important department of the steel plant. Unfortunately, within six months, my father suddenly died and so that project was abandoned. When I came back to Bombay, under the constitution of Tata Sons, the three partners – Dorabji, Sir Ratan and my father, who were equal partners and were permanent directors – had the right to appoint a successor. The successor who will be a permanent director in his time and who would himself have the right to appoint a successor. After that, there would be no more. Since my father had appointed me in his will, I automatically became a director of Tata Sons. Sir Dorab Tata, who was then chairman, fixed my remuneration at Rs. 1000 a month.

Rs. 1000 a month?

In those days, Rs. 1000 a month was very good. That’s how I returned to TISCO. I was now an employee of Tata Sons, who were then Managing Agents of all the Tata companies. It is important to understand that in those days, the Managing Agency system prevailed and the Managing Agents once having made their contract with the shareholders, had executive powers. They were in a position to appoint chief executives of every company in that contract for which they had contracted with the shareholders. Sir Dorabji Tata was the chairman of Tata Sons, the parent company, and in those days, automatically the chairman of Tata Sons became the chairman of other companies. I was supposed to be associated with Tata Sons and companies under its management. I had decided from the start that I would stick to TISCO.

"I was sent there (TISCO), with the idea that I’d spend a couple of years at Jamshedpur. Since I had not been trained as an engineer or had no formal education, I should learn the practical aspects of the steel industry."

I think, I must mention, that before my father died, he had talked to the managing director of Tata Steel who was a Scotsman, who had been a leading ICS officer in the Government of India, a very fine gentleman called John Peterson who was a most unusual man. Apart from being a fine writer – who’d even written plays in English, including one I remember that I had read called Mary Queen of Scots – which had been staged in Germany, he somehow had an aversion to Britishers.

He had an aversion to Britishers?

For some odd reason, when young Britishers came to see him, he was, I never knew why, a little hostile. But to Indians, it was as if they were his children. Unusual, I never could quite understand why. Peterson had been very friendly with my father, and on one occasion he told him, “Peterson, look after my son when I am no more.”

So when I came back from Jamshedpur, Peterson had a desk put at the end of his desk, for the next five years. Before he retired to England, he never had a moment’s privacy in the office. I was at the end of the table listening to everything. As a form of education, he made all the papers come and go through me. I learnt a lot from him, including ways to get on with people, to exercise judgement. He saved me sometimes from embarrassment.

On one occasion, a note had come from one of the other directors of Tata Sons. I didn’t know it was him, and so I had extensively corrected it. Peterson was amused. But he had a copy made without the correction. He was a wonderful man.

He is the man who wrote the first application for protection of Tata Steel. Tata Steel was in a very bad way because steel was being dumped from all countries into India – imported steel bars at less than Rs. 100 a tonne. Tata Steel was, as we know, in those days very near not being able to pay wages. On that occasion, Sir Dorabji Tata pledged the whole of his fortune and the banks came forward. I remember, Peterson wrote the main thesis justifying protection to Tata Steel, which went to Parliament, or the then Parliament. A very fine document, which succeeded thanks to perhaps Motilal Nehru and the Swadeshi Movement. I am very grateful to Peterson in being my guru of those days.

Did you make any special efforts to go up from manufacture of steel?

There was a very wonderful book written for the United States Steel Corporation called The Making, Shaping and Treating of Steel. It was a big black book, which covered the whole subject of those days. I had religiously read that book. Hence, I was pretty well aware. I had also spent six months in Jamshedpur, and I went back from time to time. The days when I could have spent the whole time in the plant, as I would have liked to, had gone by. Some years later, I became a director of Tata Steel and of course, finally, chairman, from 1938 until last year.

I believe Sir Nowroji Saklatvala was there till 1938. How did you relate to him?

Very well, he was a very fine and honest man. Having continued this principle of being chairman of every company in Tatas, he had no time to do any administrative work; he relied a fair amount on me and I was as helpful to him as possible, As soon as I became chairman, I decided that I shouldn’t be the chairman of all Tata companies. I said I will not take the textile mills. Sir Nowroji Saklatvala had really come through the textile industry. I even said I don’t want to keep the Electric Companies. I will keep only a few companies since we were creating new industries.

Did he ever ask you why?

Yes, well I used to argue with him that this was wasting his time. He had to attend every board meeting, go through all the minutes, go from one meeting to another. It is all right for general supervision; you should not be the chairman of a company unless you have time to give to it.

How did it feel like to be elected chairman of the Tatas at the age of 34? You have referred jokingly that your senior colleagues in a moment of mental aberration elected you chairman. Were you prepared for the eventuality? You knew that you were going to be the Chairman and were you prepared for it?

No, in fact I didn’t. I realised that they had some difficulty. Anyway, they decided that I would do, even though I was reluctant, I had but to say yes, thank you very much.

Originally published in Sands Of Time, a newsletter by the Tata Central Archives

Photographs courtesy Tata Central Archives