796 words | 3-minute read

“We shall overcome, we shall overcome, we shall overcome, some day;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome, some day.”

The haunting tune of the legendary protest song of freedom movements around the globe rings through the courtyard of the Eklavya Model Residential School (EMRS) at Mundhegaon in Igatpuri taluka of Maharashtra’s Nashik district.

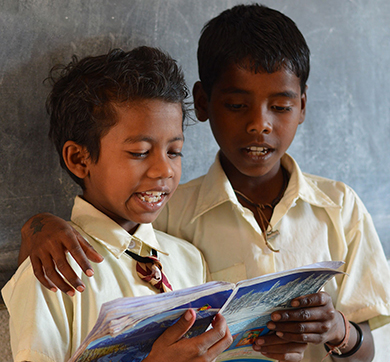

Some 40 girls of the school, belonging to impoverished families living in the state’s hardscrabble tribal belt, evocatively render the powerful song. More than 500 students, boys and girls, are studying at the residential school meant for tribal children. For most of their parents, toiling away in harsh fields, or working as migrant labourers in distant cities, it was a bold decision to leave their children at the residential school.

The students get quality education, accommodation in hostels, and, most importantly, nutritious meals.

The Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, provides funds to state governments to run EMRS and residential ashram schools for the benefit of members of the scheduled tribes. In Maharashtra, there are four English-medium Eklavya residential schools, including the one at Mundhegaon.

In June, the Maharashtra government signed a memorandum of understanding with the Tata Trusts and Bengaluru-based NGO Akshaya Patra to set up two centralised kitchens – called Annapoorna kitchens – in Mundhegaon and Kambalgaon in Palghar district. The unique public-private partnership aims to provide wholesome food to students at EMRS and ashram schools in the state.

Says Manoj Kulkarni, the Tata Trusts executive in charge of the Nashik and Palghar kitchens: “The modern centralised kitchen, featuring state-of-the-art equipment, has a capacity for 20,000 meals a day. At present, we cater to the needs of 3,500 students at this school and in nine other institutes, including ashram schools, within a radius of 50km from here.”

The kitchen is funded by the Tata Trusts and Akshaya Patra is the technical adviser for the project. Says Shivaji Patil, an assistant teacher at the school: “Many of these students come from villages where malnutrition is an endemic problem. The healthy food they consume here has energised them, improving their performance in class.”

The Mundhegaon school building and campus are indeed impressive. Previously, the school operated from a rented premise in Nashik, but last year, the students shifted into the brand new campus.

The wholesome food is definitely a game changer. Says Manisha Bhairav, an eighth standard student, “I like the food that is served; it is very healthy. Our teachers tell us to eat more vegetables.” Manisha, whose parents are farmers, speaks confidently in English, a language no one in her family is familiar with. She hopes to become an engineer.

Like Manisha, Lata Sasane, who has just finished her lunch and is eager to join her friends in the playground, appreciates the quality of the food. Her parents, too, work in the fields at a distant village. Lata would like to be a teacher, she says coyly. Hemant Khade, also in eighth standard, would like to become a software engineer. “I will go to college in Nashik and do my engineering,” he says.

The students squat on the floor in a large hall and enjoy their meals. The food is simple – chapatis, vegetables, rice and dal. The servings are large and the growing children eagerly consume the food. Later, they wash the utensils and return them to the kitchen.

The school’s central kitchen has four rice cauldrons, each with a 600-litre capacity. Two more cauldrons for dal, each of 1,200-litre capacity. Mr Kulkarni emphasises on the hygiene aspect. Anyone entering the kitchen has to wear a hair net, use a hand sanitiser, and ensure that cleanliness is maintained.

“We also have quality control personnel checking the content and the places where the foodgrains and vegetables and other inputs are stored,” he says. “We follow all good manufacturing practices.” The kitchen is washed thoroughly and even the mini-trucks that carry the meals to distant schools are cleaned before the food packets are loaded.

Having grown up in remote villages, many of the students are not familiar with the food that is served. Mr Kulkarni recalls that when the kitchen began serving idli and sambar (a popular south Indian dish) for breakfast in October, most students were reluctant to touch it as they had never seen the dish before.

“They drank the sambar but refused to touch the idlis," he recalls. “I had to tell them that it is a popular item in south India and is nutritious and good for health.” Of course, now they eagerly eat idlis and many of them can finish off six in one sitting. That is the kind of feedback that leaves a good taste in the mouth for all concerned!

—Nithin Rao