January 2021 | 2610 words | 10-minute read

The planned merger of Tata Global Beverages and the consumer products division of Tata Chemicals came in to effect in February 2020, presented a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for an organisation.

Mr Sunil D’Souza, who in December 2019 was appointed CEO and MD of the new enterprise, christened Tata Consumer Products (TCPL), says, “If we got it right, the rewards would be endless. If we didn’t, we’d have to live with it for a long time. We are creating a structure to solve for the integration today. But it has to be done in a manner that we would be able to seamlessly absorb changes as we grow.”

Seven months later, with Tata Consumer Products becoming the third most valued company in the Tata group, the TCP team seems to have made the right beginning. The goal was to bring together two disparate but individually successful businesses to lay the foundation for a fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) powerhouse, and build towards common processes, structures, people, systems, and deliver synergies on cost and revenue.

Merging in the time of Covid-19

What the newly formed Tata Consumer Products hadn’t anticipated was a merger and integration in the throes of a pandemic. “We had prepared for the challenges of integrating and creating the right platform for future growth, but I had not bargained for being confined to a room and taking over remotely,” says Mr D’Souza.

Undoubtedly, a smooth integration — while keeping people at the centre — was priority; but given the pandemic situation, the company had to get their distribution systems and logistics moving to service retailers and reach consumers. Since TCP’s products constitute essential services, some aspects were relatively easier to overcome. For the rest, Mr D’Souza credits the strength of the brand, along with the passion and determination of employees for the company’s successes through the pandemic.

“Figuring out permits and when they’re required, reaching consumers during the lockdown, finding innovative solutions for labour when it isn’t available, planning remotely to ensure supply chains aren’t disrupted, having the beverages distribution step in when the foods business needs it and vice versa, all pre-integration. It’s the strength and passion of our people that stands out at the Tata group,” he says, adding, “Earlier, as an outsider and a consumer of Tata brands, I knew about the strength of the brand and its capabilities, but I saw it play out during the lockdown. The ability to draw on the resources of different group companies, and the data science ecosystem helped solve problems and find new opportunities.”

People at the forefront

An impending merger can be a source of stress or uncertainty for employees. However, TCP kept people at the front and centre throughout the integration process. Amit Chincholikar, global chief human resources officer, TCP, says, “Our approach was to keep everything transparent from the time integration was announced in February. Our messaging for the leadership was around the big picture — to be part of an exciting journey towards creating a premium FMCG company. For the middle management and employees at the entry level, we focused on how the integration would create more opportunities. For instance, those engaging with a dealer or distributor, would have more leverage with them because they would have two hefty portfolios — food and beverages — instead of one.”

The steady two-way communication flow has ensured that employees have clarity on their goals and deliverables. “The whole organisation knew that this was an opportunity for us to create a world-class FMCG consumer platform that would enjoy the trust associated with the Tata name,” says Mr Chincholikar. “This has reflected in people’s actions, and ultimately, in our numbers. For example, in May, at the height of the pandemic, we had the highest ever production from our tea factories, which means people were acutely aware of their responsibilities and what it meant.”

As a result of the integration, there were scenarios where some employees who were part of the food business now had a manager who was once working for the beverages business and vice versa. This supported a better integration from a culture and ‘ways of working’ perspective. It also advocated the clear plan that the company had for identifying critical talent and demonstrating a clear growth path for them.

Mr Chincholikar says, “Roles being assigned to people are increasingly being aligned to where the organisation sees them in three to five years. You don’t recruit for the here and now; you recruit for leadership potential for the future.”

2X distribution power

One of the most significant outcomes of the merger is the combined strength of the food and beverages (F&B) distribution networks. “The increase in our market reach is the biggest impetus from the merger,” says Richa Arora, president, Packaged Foods (India), TCP.

Mr D’Souza says the goal during integration was to create a sales and distribution system for the future; this involved delayering, expanding reach, doubling direct distribution in 12 months and layering on top of it, to double our total numeric reach in 36 months.

Currently, the company reaches directly to outlets through its distributor salespersons, as well as by advertising its products, thereby creating wholesale pull. “For newer categories like Tata Sampann dals (pulses) and spices, one needs a bit of hard-selling. We’ve increased the number of distributor salesmen by 1.5x, who will help double the outlets we touch directly. And then we keep powering the brand through advertising and promotion, in addition to the wholesale multiplier, to get to 2X total reach in 36 months.”

TCP plans to leverage the consolidated distribution system of Tata Tea and Tata Salt, on which some smaller brands can piggyback. “The equity that our flagship brands have allows our distributors to cross-sell Tata Sampann dals and spices when they connect with their outlets,” says Mr D’Souza.

Direct distribution plays a critical role in promoting innovation, according to Sushant Dash, president, Packaged Beverages (India, Bangladesh and Middle East), TCP. After the beverages division, with its reach of two million outlets, was integrated with the distribution network of the food business, it gave the company a larger size of business. “Through indirect coverage, it is easier to sell products that already have a strong recall for the consumer, but premium or niche products get missed out. These products have penetration through direct coverage because your distributor buys it and spends time and effort upselling to the retailer. Newer products have a better chance of success.”

Distribution patterns have also been influenced by trends like online shopping, which has seen an upswing since the outbreak of the pandemic. “The contribution of ecommerce and the online channel to sales has doubled from about 2-2.5% to 5% during this period,” says Mr D’Souza. “We quickly adapted to the trend and built a dedicated e-commerce vertical; we’re also partnering with other platforms or retailers who have the ‘Click and Buy’ option.”

Before the pandemic struck, the Foods business had started Nutrikorner, their content to commerce platform focused on celebrating Indian food wisdom. Sharing information on immunity-building, food safety and hygiene through expert voices in the food and health domain, ranging from chefs, doctors, ayurvedic specialists and nutritionists, it is the leading online food platform with over five lakh page views per month. Today, it is working towards strengthening the direct-to-consumer commerce part of the platform, in response to the need to drive product access through digital platforms during the lockdown.

Expanding operations

Manufacturing units have historically been located at the source of raw materials but even before the merger, things were changing at the foods business. “Our manufacturing centres were in south India, as we could both access a wider variety of spices and tap into the knowledge of experts in the industrial base there,” says Ms Arora. “But as business expanded, we have set up manufacturing operations closer to the source of specific spices, like Gujarat for coriander and cumin and Andhra Pradesh for chilli.”

Packaging units are being expanded closer to demand hubs. Spice packing operations are starting soon at a facility close to Mumbai, as it offers quick access to metro markets.

Similarly, units for pulses have always been situated closer to sourcing hubs concentrated in central and western India. A year ago, the Foods business started pulse packing operations at the company’s salt packing centres in Kolkata and Bangalore. “We are looking to expand these further as we scale up and build demand in key metro markets,” says Ms Arora. “Manufacturing strategy will be driven by total value chain cost — existing demand hubs and emerging demand.”

A taste for health

Health is a megatrend being observed across the F&B business. “We’ve launched variants across our brands that play into that. Our tulsi (basil leaves) tea blend that we launched via e-commerce is doing really well,” says Mr Dash.

Catering to personalisation in taste, the beverages business launched Tata Tea Quick chai in ginger and masala flavours for an instantly brewed but indulgent cup of tea, while Tetley rolled out a series of fruit flavours that appeal to the health conscious and to those looking for personalised flavours.

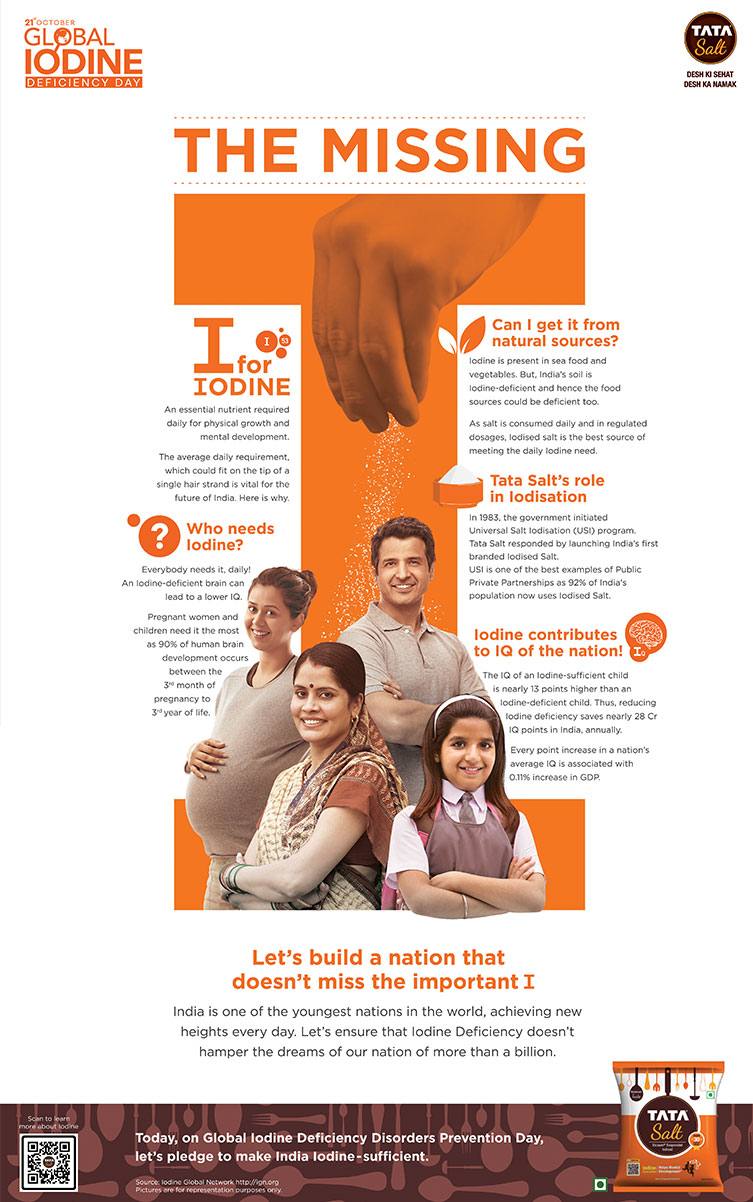

For the food business, health has been a focus since the first branded iodised salt, Tata Salt, was launched in 1983, to address the then prevalent iodine deficiency in the country.

“The DNA or ethos of Tata Salt has always been as health keeper of the nation,” says Ms Arora. “Not just because of the genesis of the brand, but also through the years, we’ve launched healthy products like low-sodium salt.”

This approach to address larger societal or health issues in the country has come full circle with Tata Sampann — Tata Consumer Products’ range of spices, staples like pulses, poha and ready-to-cook offerings — which has always been positioned around the natural goodness of its offerings. Its appeal has grown further since the pandemic. “Consumers have reduced discretionary spending and turned to spending on health food and fitness or wellness products,” says Ms Arora. “We are seeing a strong revival in traditional Indian food wisdom and home cooking, and a preference to go back to one’s roots and lean on traditional ways to build long-term immunity.”

Tata Sampann appeals to more progressive, urban homemakers, who are discerning about changing health concepts. “The conversation around health, fitness and food has been centred on subtraction — subtracting food groups, calories, portion sizes, etc, which may not be sustainable and also raises questions regarding the impact on long-term health and suitability for indigenous populations,” explains Ms Arora. “Food should be associated with wholesomeness, not subtraction. It’s about the right balance of proteins, carbs, fats and other nutrients which the body needs. Tata Sampann offers real health and fitness, by enriching everyday foods and making them ‘Sarvaguna Sampann.’

Marketing national pride

An enduring brand not only fulfils a need or a function, but also makes an emotional connect. Tata Salt remains one of India’s most beloved brands because it has pioneered the movement to bridge the micronutrient deficiency gap in India, as the first branded iodised salt. “We became Desh ka namak because we consistently delivered high-quality salt,” says Ms Arora, adding, “Our marketing strategy has always been to celebrate the nation and its health, and our latest campaign, Sawaal Desh Ki Sehat Ka, remains true to that.”

For the beverages business, the strategy has been to connect with consumers by going hyperlocal in blends, packaging and communication. Consumers have a strong sense of pride in their local cultures; in fact, regions within states have their typical consumption traditions.

And, Tata Tea brands like Tata Tea Premium, Tata Tea Gold, Tata Agni and Tata Elaichi acknowledge and celebrate cultural differences. Tata Tea Premium, for instance, launched specific packaging celebrating regional pride. “We have different packaging for Tata Tea Premium in Delhi, Haryana, Punjab, Orissa and Madhya Pradesh,” says Mr Dash. “More than the packaging, it was also about what we promised in terms of blends, as people in different states prepare their tea differently.”

Tata Tea Gold, the market leader in West Bengal, had a brandnew packaging that celebrated Durga puja. In Bihar, packs were changed to incorporate Madhubani art and mark Chhath puja; while Tata Tea Chakra Gold, hugely popular in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, was adapted to colours and design that TCP’s research showed would be popular in the region.

Trans-generational appeal and the digital bridge

Tata Salt’s brand book says: Every hand that reaches for a morsel of food also reaches for a pinch of salt. For a brand that caters to approximately 700 million consumers every year, the positioning strategy cuts across socio-economic and demographic segments, including age groups. “The key is reaching this diverse audience through relevant consumer touchpoints,” says Ms Arora. “We reach a younger audience through digital campaigns. Our share of digital spends has been increasing over the years because as a medium, it helps us innovate and create contextual communication.”

The beverages business was one of the first to adopt digital and social tools to connect with the youth, during the early days of the Jaago Re campaign in 2007. “That initiated two-way communication,” says Mr Dash. “It was about having conversations with consumers, and one of the reasons the campaign has been a success is because of the growth of social media and digitalisation.” Today, many of the brand’s campaigns are digital-first.

Global trends: Health, sustainability and discovery

The company has been a significant player in the international beverages market, ever since Tetley became a wholly owned subsidiary of Tata Global Beverages in 2000. The heritage brand enjoys iconic status in the UK, where it is the number one brand according to household penetration. It is also the number one tea brand in Canada, and has a presence in markets across the US, Australia, Middle East, South Africa and Europe. Along with American brand Eight O’Clock Coffee — immensely popular on the east coast of the US — Tetley makes up a large chunk of the Rs 3500 crore international market for Tata Consumer Products.

The brand has successfully stayed ahead of the curve by adapting to emerging trends, one of the biggest of which is the diminishing popularity of black tea overseas — the product that brought Tetley its fame and reputation. “There is a disadvantage to having a brand that is so heavily indexed on a category that is slightly declining over time,” says Adil Ahmad, president – International Business, TCP. “But we have adapted to the other trends. One of these is health and wellness, which is sweeping the globe, spearheaded by younger consumers who seek fortified, better-for-you hydration products. Another is the indulgence for discovering or trying new things.”

Another trend is sustainability, wherein consumers assess whether products are ethically sourced, have a responsible supply chain and a low carbon footprint, whether in terms of the packaging or the product itself. The fourth major trend in the global markets is non-alcoholic adult beverages like iced tea, cold coffee, kombucha and an Ecuadorian rainforest tea called guayusa.

For the more mature western markets, TCP has come up with a host of ready-to-drink herbal teas, Tetley Cold Infusions, and kombucha, which was launched under the Good Earth brand. “Our whole innovation engine is geared towards non-black tea innovation as well as sustainable packaging,” says Mr Ahmad. “But the base business (black tea) will always be the short-term growth driver because it is 75 to 80 percent of the business. There will always be a degree of reinvesting in the base business — equity, advertising campaigns and sustainability.”

—Anuradha Anupkumar & Sanghamitra Bhowmik